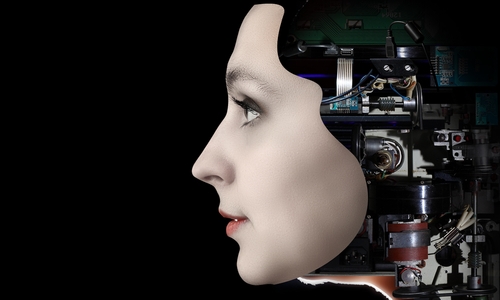

Artificial Intelligence: New challenges for the legal profession

Artificial Intelligence throws up a range of legal issues, says Luis Franco of Pérez-Llorca.

Olga Nikonova Olga Nikonova

The idea of Artificial Intelligence (‘AI’) has been around since the times of antiquity, even if the actual term was coined centuries later at Dartmouth College in 1956. Certainly, we find many examples of thinking machines in ancient myths and, in more recent years, the literature and film industries have recurrently drawn upon that idea to create all kinds of stories. And, ultimately, that is how many people see AI: as an idea bound up with the realm of myths and science fiction.

However, this preconception may soon change considering some of the recent developments in this area. Self-parking cars are already available on the market and according to major car manufacturers’ expectations, self-driven cars will arrive in 5 to 10 years’ time. Unmanned aircrafts and drones are becoming increasingly common in many fields (border control, package delivery, etc). We also have several examples of programmes with certain learning capabilities: web ads, search engines like Google Search or apps like Siri and Viv which use a natural language user interface, adapting to the user's individual language usage and individual preferences with continuing use and returning individualized results).

Certainly, the opinion of a significant section of the scientific community seems to be that AI will arrive shortly, considering that in the past few months several renowned scientists have emphasized the risks of AI and the need for worldwide regulation on the subject. The best example of this is the open letter recently published by the Future of Life Institute (“FLI”), which has been signed by a number of respected scientists including Elon Musk (co-founder of PayPal, Tesla Motors and SpaceX) or preeminent astrophysicist Dr. Stephen Hawkins.

The letter includes a list of research priorities which put forward several interesting and complex questions requiring an adequate solution. We do not presume to have any or all of the answers but we would like to outline some of the most complicated aspects and propose some additional questions to consider.

Short term horizon: autonomous systems

Considering the short term research priorities set out in FLI’s letter, what we can hope to expect from AI in the near future are increasingly autonomous systems, such as self-driven cars, autonomous trading systems, more efficient information managing programmes, fully automated factories, etc. From a legal perspective we would be interested in exploring one of its most fundamental aspects, which is potential liability in the event of damages caused by an autonomous system.

FLI’s letter addresses this issue in connection with liability for accidents caused by self-driven cars (although this concern could be extended to drones and other automated vehicles).

Firstly, who exactly should be taking out the premiums of the obligatory insurance policies associated with the vehicle? The ratio legis behind mandatory insurance policies is that a motor vehicle is inherently dangerous and, thus, its owner must guarantee cover for any damages caused by it. However, if control over the vehicle is taken from the owner and given to an autonomous system, it could be argued that it should be its manufacturer who bears the cost of the insurance policy, or perhaps that it should be shared between the manufacturer and the owner.

A different question would be the actual allocation of liability in the event of an accident. Assuming that all control over the vehicle is taken away from the driver (for lack of a better word), how could he/she be held liable for the damages caused in an accident? Thus we need to explore the potential liability of the manufacturer.

If the damages were caused due to a faulty design malfunction and/or assembly of the vehicle, the matter does not present any particular complexity, as in such an event it is clear that the manufacturer should be held liable.

However, liabilities cannot be so easily allocated if no malfunction is involved in the accident. For example, if a system which is working properly detects a potential risk but cannot react fast enough, current legal doctrine would dictate that no liability should be allocated to the manufacturer if the system was working in accordance with current scientific knowledge and technology and had been approved by the relevant public authority.

Considering the above, the standards set by the public authorities in order to approve any given autonomous system will have to be carefully measured. In order to set these standards, a consideration of paramount importance and great complexity is how a system should ponder the potential risk of causing injury to a person versus the risk of causing economic damages.

Obviously, human life and health should always be prioritised over property damage. Thus, when probabilities are levelled, the system should avoid the chance of causing personal injury and assume the risk of causing economic damages. However, if the probability of causing personal injury is very small, the answer might be different. Indeed, if we took the avoidance of risk to humans to extremes, we could reach a point where no system would operate, since there would always be such a risk. However, there is a huge grey area in the middle, where several factors should be considered in order to set boundaries (which would constitute a sorites paradox).

Of course, there are many other questions that autonomous systems will bring up from a legal perspective. For example, issues related to privacy and security of personal data (can autonomous systems share personal data?) or labour-related matters.

Long term: sapient, self-aware systems?

In the long term, the questions and challenges will become far more complex and challenging as they will exceed the boundaries of both computer science and laws and will enter into the territory of ethics, philosophy and even religion, similarly to other highly controversial fields of scientific investigation, such as human cloning, stem cell research or genetic engineering.

If a truly sapient machine could ultimately be created - which in view of FLI’s letter seems conceivable-, it will likely be a turning point in human history. The potential benefits (and indeed risks) are immense, and a lot of them may probably be far beyond what we currently consider as even remotely possible as will be the questions that will need to be answered.

Indeed, we may have to consider if such sapient machines should have a legal (cybernetic?) personality and whether they could be held liable. We may also have to ask ourselves if those machines can own property and have other civil rights or, even, if they can be actually owned or, on the contrary if owning a truly sapient, self-aware, creature -even if an artificial one- would be tantamount to slavery.

Perhaps some of these ideas might seem far-fetched, and even somewhat shocking, however, rather than providing any answers, these are merely questions that the legal community and other professionals should begin to think about.

New questions

The development of Artificial Intelligence, which is likely to speed up in the near future, will bring forth new and complex questions to which no legal system in the world has an answer. It is therefore necessary for the legal community to begin to consider the answers.

Luis Franco is a Litigation and Arbitration Lawyer at Pérez-Llorca

Email your news and story ideas to: [email protected]