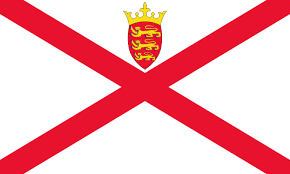

Jersey

Family Asset Protection: Divorce, Finance and the Media

Introduction

The Bailiwick of Jersey is one of the three Crown Dependencies of the British Crown that surround the United Kingdom. It is located in the English Channel, sixteen miles west of the French Normandy coast. It is not part of the United Kingdom’s territory and has never been absorbed into the common law legal system of England and Wales, having been a self-governing territory for over 800 years, enjoying virtual total autonomy over its own taxation, legal system and domestic affairs.

Jersey’s legal system has its roots in Norman customary law but has also been influenced in varying degrees over the centuries by English law and French law. Jersey’s law of trusts is governed principally by the Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984, as amended. Its matrimonial law is governed by the Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949. In the absence of local legal authority or legislative provision, Jersey will often look to judgments of English and Commonwealth courts as being persuasive (Re Malabry Invs Ltd 1982 JJ 117). Local legislation is enacted by Jersey’s parliament, the States Assembly. Assent to local statutory law is effected through the Privy Council in London.

Jersey is not a part of European Union and is not subject to EU law. Therefore, EU Regulations concerning jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil or matrimonial matters.

The family court (the Family Division of the Royal Court of Jersey) has jurisdiction in relation to divorce, nullity and judicial separation (Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949, Articles 3 and 6) where:

- the parties are domiciled in Jersey when proceedings are commenced;

- either of the parties was habitually resident in Jersey for the year immediately preceding the date proceedings are started.

The same jurisdiction rules apply for both mixed and same sex spouses and civil partners.

Financial remedies are generally applied for within divorce proceedings. Claims can be made for:

- Periodical payments (for children and spouses).

- Lump sum payments (with security as necessary).

- Property transfers.

- Orders for sale of property.

- Variation of nuptial settlements.

- Interim orders.

The Royal Court does not currently have jurisdiction to make a pension sharing order in matrimonial proceedings although, in practice, that is often compensated for by making provision from elsewhere in the matrimonial ‘pot’.

1 . Divorce and trusts

Jersey is one of the foremost offshore jurisdictions in the world for private wealth structuring using trusts. Jersey law recognises trusts whether governed by Jersey law or trusts established and governed by laws other than Jersey law. Jersey is a party to the Hague Trusts Convention.

It has a very well-developed case law concerning trusts and trust disputes and Jersey’s principal court, the Royal Court of Jersey, and the Jersey Court of Appeal are recognised internationally as a pre-eminent source of leading modern trust jurisprudence.

A common issue in play in matrimonial proceedings involving Jersey is whether any resulting matrimonial award can be enforced against a trust in Jersey. Jersey has enacted legislation in Article 9 Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984, (known as the ‘firewall’) specifically to protect Jersey trusts from by interference of orders of foreign courts.

Where there is matrimonial claim to: i) vary a Jersey trust; ii) claim trust assets as part of a matrimonial award; or iii) treat a trust as belonging to a spouse or otherwise being a ‘financial resource’ from which maintenance or a lump sum is to be satisfied, the treatment of the trust assets could be subject to a range of analyses:

- Whether the trust is a nuptial settlement that is capable of being varied or subject to a property adjustment order under the jurisdiction of the matrimonial court (e.g. under section 24(1)(c) Matrimonial Causes Act 1974). This involves affirming the existence of a genuine trust. Where the trust is governed by Jersey law, and variation is sought as a remedy, early and careful consideration will be required as to whether any order made by a foreign court is capable of enforcement within Jersey. Where potential enforcement will be against a Jersey trust, the firewall legislation in Article 9 Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984 will be engaged.

- Consideration (particularly if the matrimonial proceedings are outside Jersey and the trust assets within the jurisdiction of the matrimonial court) will often be given to whether the trust can be established as being a sham. An allegation of sham against a Jersey trust goes to the validity of that trust and again, early consideration of Jersey’s firewall legislation must be considered. An allegation of sham entails a finding that the parties to the trust dishonestly intended to present the trust as genuine.

- Whether the trust assets can be attributable to the settlor/beneficiary in another way, e.g. whether the way the powers and beneficial interests in the trust are arranged is such that the settlor/beneficiary has de facto control of the assets and has rights that are, in substance, equivalent to ownership e.g. Pugachev ([2017] EWHC 2426 (Ch)). The Jersey courts have never had to rule upon the analysis employed by Birrs J in the case of Pugachev. Whether the firewall would protect a Jersey trust from such an analysis remains an open question.

1.1. Financial disclosure

The financial disclosure obligations of a spouse in divorce proceedings filed in Jersey relating to their trust interests on a worldwide basis would be as follows:

- Each party to divorce proceedings must, following the preliminary directions hearing, file and serve an affidavit of means containing full particulars of all property, income and expenses of each party. This includes any interest either spouse has under a trust, located anywhere in the world, whether that interest is vested or contingent.

- The disclosing spouse is obliged to state the estimated value of their interest under the trust and state when, if ever, that interest is likely to be realisable. An interest under a discretionary trust must be disclosed. If a spouse believes that the interest may never be realisable or has (in the present or future) no value, they must provide their reasons for that assertion.

- In order to engage the Royal Court’s jurisdiction under Article 27 Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949 (the power of the court to vary a nuptial settlement), the particulars given about a settlement should include (or can be asked about in any subsequent questionnaire that follows receipt of the affidavit of means) the basis upon which the settlement was established and the circumstances by which it is said to have ‘nuptial quality’.

The financial disclosure obligations of a trustee in divorce proceedings filed in Jersey where the trust is governed by Jersey law are as follows:

- Whether the divorce proceedings are commenced in Jersey or whether they are commenced outside of Jersey, unless the trustee submits to the jurisdiction of the divorcing court and is made the subject of an order for disclosure about the trust, there is no obligation of financial disclosure concerning the trust that is imposed upon the trustee simply because a beneficiary is going through a divorce.

- There is no standard way in which a beneficiary’s interest can be structured under a Jersey trust. A beneficiary may have a fixed interest or can be an object of the trustee’s discretion to apply income or capital in their favour, as is the case with a discretionary trust. It may be a mixture of the two.

- Whether or not the trustee submits to the jurisdiction of the divorcing court, when divorce proceedings are in prospect and one or both of the divorcing spouses is a beneficiary of the trust, the trustee should seek Jersey advice on whether it wishes to exercise its discretion to provide financial information concerning the trust and the beneficiaries’ interest under it. The trustee’s discretion to provide information and disclosure about a trust is independent of the divorce proceedings.

- A focused disclosure exercise of relevant information about a trust may, in the right circumstances, serve to head off what might otherwise be a credible threat to the trust and its assets posed by divorce proceedings. The trustee will need to make a decision (which it may also seek to have ‘blessed’ by the Jersey court) whether to provide financial information at all and, if so, what information, to whom, under what conditions (e.g. a confidentiality ring). This will always be fact specific exercise.

The financial disclosure obligations of a trustee in divorce proceedings filed in a foreign jurisdiction where the trust is governed by Jersey law would be as follows:

- A Jersey trustee has no obligation to provide disclosure about the trust or a beneficiary’s interest under it simply because a beneficiary requests the trustee to provide disclosure. The trustee retains an independent discretion concerning whether, and if so what, to disclose to a beneficiary upon request.

- The tension that exists in answering any request for disclosure of information by beneficiaries is a balance of a number of factors: maintaining the confidence of the beneficiaries that the trustee is accountable; the trustee’s duty of confidentiality to and between beneficiaries as a whole; the trustee’s duty to preserve the trust fund from potential attack by a hostile party; and, lastly, the value the trustee may ascribe to maintaining a ‘safe space’ in which it is free to exercise its discretion and decision making without constant interference from beneficiaries.

- Jersey law has long recognised that the disclosure of trust information and documents is subject to an overriding judicial discretion and not hard-and-fast rules as to the beneficiaries’ unassailable right or entitlement to documents or information. This discretion forms part of the court’s overriding supervisory jurisdiction in relation to trusts and enables the court to intervene, where necessary, to protect the trust from an attempt by beneficiaries to obtain information that may be contrary to the interests of the beneficial class as a whole. (The leading Jersey case on the disclosure of trust information by trustees is Rabaiotti 1989 Settlement [2000 JLR 173]2); the approach adopted was later endorsed by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the leading English decision of Schmidt v. Rosewood Trust Ltd [2003] UKPC 26, affirmed in Jersey by Re Internine Trust [2004 JLR 325].)

- The leading Jersey case law governing the principles applicable to the disclosure of information and documents to beneficiaries by trustees predates the current formulation of Article 29 Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984. In 2018 Article 29 was replaced in its entirety by a provision which better articulates the position that had been reached in the case law prior to its enactment.

- Article 29 now expressly provides that a beneficiary’s prima facie entitlement to request any document which relates to or forms part of the accounts of the trust is subject to contrary provision in the trust instrument itself. A blanket prohibition in the trust instrument on the beneficiaries’ access to accounts and information is very likely to be held to be ineffective.

- The key issue is whether restrictions in the trust itself on what may be disclosed encroach upon the overarching supervisory jurisdiction of the court.

Efficacy of foreign orders for disclosure

The order of a foreign court made directly against a Jersey trustee to provide disclosure about a Jersey trust is not enforceable against the trustee in Jersey. That is not to say such an order does not have effect in the jurisdiction in which it is made and a Jersey trustee that has any exposure to the jurisdiction of the matrimonial court may regard themselves as being bound by such an order regardless of whether the order is directly enforceable in Jersey.

A Jersey trustee caught between its duties of maintaining the confidentiality of the trust and a foreign order requiring disclosure will often seek the protection of the Royal Court for directions as to what it should do. The Royal Court may direct the trustee as to what disclosure and information it should provide in compliance with a foreign order for disclosure. A trustee who acts in accordance with such a direction cannot later be sued by the beneficiaries for breach of trust or confidence.

Letters of request

The principal means by which an order for disclosure against a Jersey trustee by a foreign court is given domestic effect in Jersey is by way of letters rogatory, or letters of request.

Part 2 of the Service of Process and Taking of Evidence (Jersey) Law 1960 provides for the taking of evidence in Jersey in proceedings held outside the island (referred to as ‘the requesting court’). The Royal Court has a wide discretion to make such provision as it deems appropriate. This usually involves the production and transmission of documents from Jersey to the requesting court or for evidence to be taken in Jersey and that evidence to be transmitted and admitted in the foreign proceedings. Practitioners wishing to issue a letter of request to Jersey should contact local Jersey lawyers for advice as to the form and content of a letter of request which must satisfy a number of requirements. A letter of request that is too widely drawn, or strays into areas access to which is forbidden by the law of Jersey, may have those offending sections exercised or rejected (Wadman v. Dick (n 224)).

1.2. Financial orders

Obligations of a spouse beneficiary of a trust governed by Jersey law who is a party in divorce proceedings in which they have been ordered personally to pay income and/or capital to their spouse

A beneficiary that is ordered to pay income or capital to their spouse on the basis of a finding (or an assumption) by a matrimonial court that they can satisfy such an order by requesting a distribution from the trustee is in an invidious position.

In the absence of a power in the terms of the trust itself that is capable of overriding the powers of the trustees; a discretionary beneficiary of a Jersey trust generally has no power to force the trustees to make a distribution to them.

Even if a trustee was agreeable to making a distribution to a beneficiary to help satisfy a matrimonial award, a trustee may regard it as an abuse of its powers of distribution (and leave them open to an accusation of having acted in breach of trust) to make a distribution to a beneficiary knowing that in doing so the distribution will, in fact, end up in the hands of the beneficiary’s spouse (who may not themselves be a beneficiary). Depending on the size of the award, the trustee may come under pressure from other beneficiaries not to make a distribution if that would diminish the overall size of the fund. The trustee may well wish to seek the protection of the Jersey court by seeking directions as to how it should proceed.

Recent Jersey authority Kea Investments Ltd v. Watson [2021] JRC 009 has confirmed that it is not possible for a judgment creditor, such as a spouse with an unsatisfied matrimonial award, to obtain execution against the interest of a discretionary beneficiary under a Jersey trust.

A matrimonial court may have reached the conclusion that a Jersey trust is a financial resource because of a lack of candour about the true nature of the spouses’ interest and the court makes an adverse inference against them. Such a finding may also arise simply from a lack of relevant information, absent any issue of lack of candour. Disclosure about the trust and what the trustees are likely to do in response to a request from a beneficiary is therefore likely to be crucial to running (or defending) a case based on a Jersey trust being a financial resource available to a spouse in any case where that point is not expressly conceded.

To treat an interest in a discretionary trust as an asset for distribution in proceedings for a financial remedy, the court must conclude that the trustees “would be likely to advance the capital [in the trust to the spouse] immediately or in the foreseeable future“ (see Charman v. Charman (No 2) [2007] EWCA Civ 503). The objective is to establish what the trustees are likely to do.

In English law it has been held to be wrong to put undue pressure on trustees to act in a certain way by making an award against a spouse in the expectation that the trustees will have little option other to assist the beneficiary meet their obligations. (A v. A and St George's Trustees Ltd [2007] EWHC 99, Munby J). The distinction between determining what the trustees will do and this sort of ‘judicious encouragement’ to do something is almost inevitably blurred.

While it may have the effect of putting pressure on the way a Jersey trustee would ordinarily go about its duties, judicious encouragement is not a direct interference with the way a Jersey trust operates and is not something that engages the firewall legislation. The firewall is in place to protect the trust from the external interference of a foreign court, it does not protect beneficiaries from having orders made against them that they cannot satisfy without the trustee’s assistance.

Obligations of trustees of trusts governed by Jersey law with regard to court orders made in divorce proceedings filed in Jersey and requiring payment of income and/or capital

The Royal Court’s jurisdiction to make an order varying the terms of a nuptial settlement is narrower than exists under section 24(1)(c) Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. The Royal Court’s jurisdiction will only be engaged where the settlement has the necessary nuptial quality as “between the parties to the marriage”, i.e. it must confer benefits upon its beneficiaries qua husband or qua wife.

Unless the trust falls within the scope of Article 27 Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949, the Royal Court has no power to direct the trustees to exercise their direction in a particular way in favour of one spouse or another to satisfy a matrimonial order.

Where an order is made against a beneficiary as a form of judicious encouragement to the trustee, in the expectation that the beneficiary will be able to satisfy the order by asking for and being granted a distribution from the trust – answer is as in the above section.

Obligations of trustees of trusts governed by Jersey law with regard to orders made in divorce proceedings filed in a foreign jurisdiction requiring payment of income and/or capital

Any party to foreign matrimonial proceedings seeking to enforce or have effect given to a foreign judgment in Jersey that concerns a trust governed by Jersey law should be aware of the terms and effect of Article 9 of the Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984 well in advance of any final order. The practical effect of the so-called ‘firewall’ is that in respect of a Jersey trust (Article 9 applies only to Jersey law trust) the Royal Court is forbidden from enforcing or otherwise give effect to any order of a foreign court on an issue falling within Article 9(1) which are:

- the validity or interpretation of a trust (the question of whether a Jersey trust is a sham is a question going to the validity of the trust);

- the validity or effect of any transfer or other disposition of property to a trust;

- the capacity of a settlor;

- the administration of the trust, whether the administration be conducted in Jersey or elsewhere, including questions as to the powers, obligations, liabilities and rights of trustees and their appointment or removal;

- the existence and extent of powers, conferred or retained, including powers of variation or revocation of the trust and powers of appointment and the validity of any exercise of such powers;

- the exercise or purported exercise by a foreign court of any statutory or non-statutory power to vary the terms of a trust (such as section 24 Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, or section 1 Variation of Trusts Act 1958); or

- the nature and extent of any beneficial rights or interests in the property;

unless the foreign court has applied principles of Jersey law in determining its judgment on that issue.

The purpose of Article 9 is to protect Jersey trusts from interference, variation or attack by foreign courts. This was a particular concern with regard to foreign court orders in the context of matrimonial proceedings, which purported to vary Jersey law trusts (for example: section 24(1)(c) Matrimonial Causes Act 1973; Charalambous v. Charalambous [2004] EWCA Civ 1030; Minwalla v. Minwalla [2004] EWHC 2823 (Fam) (declaring a Jersey trust to be a sham).

The firewall applies regardless of whether the trustee has engaged with or submitted to the jurisdiction of the foreign matrimonial court. The Royal Court does not have any jurisdiction simply to order a trustee of a Jersey discretionary to make a distribution from a Jersey trust to satisfy a foreign order for variation of the trust or to satisfy a lump-sum order.

However, Article 9 does not prevent the court giving effect to a letter of request sent to it from a foreign court for information or disclosure of documents, even where the information that is sought for foreign proceedings pursuant to the letter of request is information that the court could be expected to refuse disclosure of were the application made to it, sitting in its supervisory capacity (J v. K and Ors [2016] JRC110).

Prior to the enactment of the current version of Article 9, the Royal Court regularly gave effect to orders of foreign courts that had the effect of varying Jersey trusts. Article 9 was first amended in 2006 with the enactment of the Trusts (Amendment No 4) (Jersey) Law 2006. Those provisions are considered in many of the reported decisions concerning the recognition and enforcement of orders against Jersey trusts made in foreign matrimonial proceedings. In doing so it has expressed the view that it regarded it an exorbitant assumption of jurisdiction for a foreign court to seek to pronounce, on the basis of its own law, upon whether a Jersey trust was a sham which the Royal Court would be very reluctant to give effect to or enforce. The Royal Court has also expressed a desire that English courts, particularly the Family Division of the English High Court, exercise restraint and refrain from using their statutory jurisdiction to vary Jersey trusts under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 and ride roughshod over the distinct supervisory jurisdiction of the Royal Court to give appropriate directions to the trustee, which, in many cases, invariably replicated the effect of an English order for variation (In the Matter of the B Trust (n 6)).

Jersey law has no equivalent jurisdiction to that conferred by section 24(1)(c) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. The Family Division of the Royal Court possesses a more limited statutory jurisdiction to vary a nuptial settlement under Article 27 of the Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949. See J v. M [2002 JLR 330] for an understanding of postnuptial settlements in Jersey law, which is narrower (and so are the Court’s powers) than the meaning of that phrase and scope of the jurisdiction to vary a settlement under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 24(1)(c).

It follows that there is no obvious Jersey law counterpart that could be applied by a foreign court so as to make the variation compliant with Article 9(1), nor an obvious reason why it would do so.

The respective functions of the foreign matrimonial court and Royal Court are different in the context of matrimonial disputes concerning a Jersey trust. The foreign court is concerned to do justice and achieve a fair allocation of assets between the spouses before it. In the exercise of that jurisdiction, the foreign court is not generally concerned to consider the other beneficiaries of the trust. The Royal Court, by contrast, is likely to be sitting its supervisory jurisdiction over the trust when the trustee returns to it for directions as to what it should do pursuant to the foreign matrimonial order. The primary consideration of the Royal Court will be to approve decisions that are in the interests of all the beneficiaries as a class, which may include one or both of the spouses (In the Matter of the B Trust [2006 JLR 532]).

The question then arises whether the Royal Court can recognise or give substantive effect to a foreign order purporting to vary a Jersey trust? It had been thought that the previous incarnation of Article 9, as the court identified in In the Matter of the B Trust [2006 JLR 532] did not exclude the possibility that the court may, as a matter of judicial comity, give effect to an order of a foreign court varying a Jersey trust. The leading reported decision on the previous version of Article 9 (In the Matter of the IMK Family Trust) suggests that the answer was yes (at least in so far as the foreign order effects a variation to a Jersey trust and not an alteration).

In IMK Trust it was held that, notwithstanding the prohibition on enforcement of a foreign order under Article 9(4), where the foreign order merely varied the trusts, the Royal Court could achieve the objectives of the foreign order, having regard to the interests of the beneficiaries as a class, under its discretionary supervisory jurisdiction. The giving of directions in this way was not said to amount to the enforcement of the foreign judgment for the purposes of Article 9(4). Conversely, a foreign order that amounted to an alteration could not be recognised or given effect to by the Royal Court as the court does not have an unfettered power to rewrite the terms of a trust outside of its statutory jurisdiction in Article 47 (In The Matter of the IMK Family Trust at [65]–[68], [78] and [80]; Compass Trustees v. McBarnett & Ors at [18]: ‘the court cannot do what the trustees cannot do’). In giving effect to a foreign order varying a trust, the Royal Court was not exercising its jurisdiction under Jersey law to vary but is actually giving directions to the trustee pursuant to Article 51 of the Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984 concerning the administration of the trust.

However, the Article 9(4) considered by the court in IMK Trust has since been amended to prohibit the Royal Court enforcing or giving effect to the order of a foreign court that is inconsistent with Article 9. The court does not retain an overarching residual power to give effect to judgments on the basis of comity in the teeth of the statute. The Royal Court now has no power to enforce or otherwise give effect to a foreign order purporting to vary a Jersey trust that falls foul of the firewall.

Since Article 9 was extended to preclude the Royal Court giving effect to any judgment not in compliance with its terms, it is no longer even possible for the Royal Court to direct the trustees, acting within the powers that they have, in a way that would give substantial effect to such a judgment (In The Matter of the R Trust [2015] JRC267A). The prohibition on the Royal Court giving effect to a foreign judgment that falls foul of Article 9 is not expressed to be limited in any way.

The Efficacy of the Firewall

The practical efficacy of the firewall very much depends upon the location of the assets and of the trustee. Article 9 operates most effectively where the trustees and the trust assets are located within the territorial jurisdiction of the Royal Court. Where the trust assets are located outside of Jersey and so beyond the jurisdiction of the Royal Court to protect them the efficacy of Article 9 is likely to questionable, particularly if the assets are immovable or otherwise subject to the territorial jurisdiction of the matrimonial court. Where assets are at risk, the trustee is likely to need to apply to the Royal Court for directions: first, as to whether it should submit the jurisdiction of the foreign court and, secondly, whether (if it has power to do so) it should give effect to the foreign order.

Relevance of the trustee’s decision to submit to the jurisdiction of a foreign court

It has been suggested that it will not generally be in the interests of the beneficiaries (as a class) for the trustee to submit to the jurisdiction of a foreign court in matrimonial proceedings in which one or both of the spouses are beneficiaries under the trust (In the Matter of the H Trust (n 6)). To do so would, on orthodox conflict of laws principles, confer a jurisdiction on the foreign court to act to the detriment of the beneficiaries who are not before it. Not submitting to the jurisdiction of the foreign court will, at the very least, preserve the trustee’s freedom of action when a foreign order is sought to be enforced, at which point it is likely the trustee will once again seek the court’s direction.

Under the current version of Article 9, submission to the jurisdiction of the foreign court is no longer the touchstone for the enforcement of the foreign decision in Jersey for judgments falling within its scope. Instead, the key question in respect of foreign judgments falling with the scope of Article 9 is whether the foreign court has applied Jersey law in its determination irrespective of whether the trustee has submitted. Of course, where the foreign order does satisfy the requirements of Article 9, the trustee, having voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction of the foreign court, will not be able to seek to argue that the order should not subsequently be given effect to in Jersey.

Notwithstanding the foreign court’s jurisdiction is no longer the central issue in respect of judgments falling within Article 9, the decision whether to submit to the jurisdiction is likely to be a momentous decision for which the trustee is usually well advised to obtain the direction of the Royal Court (In re S Settlement 2001 JLR N [37]).

The presence of trust assets within the jurisdiction of the foreign court is likely to be the most significant factor in the trustee’s decision whether or not to submit to its jurisdiction because without submission to the jurisdiction, the trustee cannot practically defend those assets from enforcement in accordance with its duties (In re A & B Trusts [2007 JLR 444]).

Whether it does or does not submit to the jurisdiction of the foreign court it has been recognised that the trustee should provide the foreign court (whether directly by its own submission or via such of the beneficiaries that do submit if the trustee does not itself submit) with the fullest financial information concerning the trust to ensure any determination or settlement is based upon the true position and not supposition (In the Matter of the H Trust).

Another factor is whether or not the trustee’s decision not to submit to the foreign court’s jurisdiction is likely to leave the trustee open to criticism and even a breach of trust claim by the beneficiaries if the trust comes to be a varied by the foreign court to the prejudice of the beneficiaries who are not party to the matrimonial proceedings (C.I. Law Trustees Limited v. Minwalla & Ors).

The issue in the trustee’s application for directions is not that the trustee needs a direction from the court as to whether it can satisfy the foreign judgment from the trust assets (the court has no jurisdiction to give that sort of direction if the foreign judgment has been reached contrary to Article 9(4)). The object of such an application is instead to enable the trustee to seek the Court’s protection from the possibility of a breach of trust action being brought against it from disgruntled beneficiaries as a result of the trustee having effectively lost trust assets in the event of enforcement being taken against them in the foreign jurisdiction.

While Article 9 does not permit the court to direct the trustee to give effect to a variation so as to give effect to a foreign judgment, the Royal Court retains jurisdiction to bless a trustee’s own decision to give effect to a foreign judgment. The approval of a momentous decision already taken by the trustees themselves is not an order enforcing or giving effect to a foreign judgment (Otto Poon [2011] JRC 167; [2014] JRC 254A). When deciding whether or not to bless a momentous decision, the court is not exercising its own discretion but is instead making a declaration that the trustee’s proposed exercise of the power is lawful and reasonable. The consideration is whether the decision falls within the range of decisions that a reasonable trustee, properly exercising its power, is entitled to make.

There has yet to be a decision as to what a trustee should do where a foreign court has made a variation order, there are assets that are vulnerable to enforcement within the jurisdiction of the foreign court, but the trustee has no power (unlike in IMK) to give effect to the foreign order and so cannot seek the court’s blessing of its own decision to give effect to the foreign judgment.

1.3. Enforcement

The Royal Court only has jurisdiction to sanction for contempt of its own orders (typically by way of fine, committal to prison or the sequestration of assets). The Royal Court will not directly enforce an order of a foreign court for contempt for non-compliance against a Jersey resident who is the subject of a foreign order.

To engage the Royal Court’s jurisdiction to grant a sanction for non-compliance requires taking a step by which the Royal Court itself makes an order which would then have to be disobeyed in order to engage the Royal Court’s jurisdiction to grant a sanction for contempt.

In the context of the disclosure of information, the Royal Court’s jurisdiction would be engaged where it is asked to grant a freezing injunction with ancillary orders for disclosure in support of foreign matrimonial proceedings. The disobedience of that order would amount to a contempt of court, punishable by fine, committal or the sequestration of assets. Likewise, where the Royal Court receives a letter of request from a foreign court for the disclosure of relevant documents and information, the mechanism by which that is given effect in Jersey is by way of order from the Royal Court. Non-compliance is ultimately punishable by imprisonment, fine or the sequestration of assets.

Where compliance with a foreign order for capital or maintenance is sought in Jersey, for the Royal Court to give effect to such an order requires that the foreign order be recognised by the Royal Court and given effect to in Jersey. That is achieved either by way of formal registration (only available for judgments from certain jurisdictions) or by means of recognition at common law. Once that process is complete, it will have the effect of making the foreign order an order of the Royal Court. Disobedience of which will be punishable by committal to prison.

Jersey, somewhat unusually, also still has a procedure to commit a person to prison for debt (an Actes à Peine de Prison). Interim orders, usually taken out on an ex parte basis and under time constraints, may make provision for a person to be arrested and held in custody until such time as he produces security for the claim which is being made. Another case is where an interim order is made against a husband where there are arrears of maintenance and the husband is an expatriate (as in Dick v. Dick). The court may also make final orders for the arrest of a debtor pending satisfaction of the debt. These orders are almost invariably made in circumstances where the debtor, although enjoying a very high standing of living, has very few, if any, assets in his own name, probably because the assets are held by companies which may in turn be owned by discretionary trusts.

In the Dick case, the ECHR held that while a draconian interim measure may well cause considerable inconvenience, in the context of the Jersey proceedings as a whole, there was no unfairness that infringed Article 6.

2 . Prenuptial and postnuptial agreements (PNAs)

A prenuptial agreement is a legal agreement made between two individuals before their marriage has taken place. A postnuptial agreement is made after the marriage. Whether pre- or postnuptial, the purpose of such an agreement is usually to set out how the couple wish their assets, income and earnings should be divided between them if they later separate or divorce.

A pre- or postnuptial agreement is not the same thing as a pre- or postnuptial settlement. This is a form of trust that is made in contemplation of marriage and benefits one or both parties to a marriage (J v. M 2002 JLR 330). The Royal Court has a limited jurisdiction to vary a nuptial settlement in some circumstances to make financial provision for the parties to the marriage or their children. Whether a trust is a nuptial settlement is often complicated and technical and requires specialist advice.

Jersey’s traditional outlook had been that an agreement entered into before or after marriage to regulate affairs on future separation or divorce would not be upheld as it was contrary to public policy. The issue of prenuptial agreements has received limited consideration by the Jersey Court. Nuptial agreements are not binding in Jersey.

The Royal Court has considered the leading English case of Radmacher v. Granatino [2010] UKSC 42 in L v. M [2017] JRC 062A, finding that a prenuptial agreement is a factor to be considered as part of ‘all the circumstances of the case’, but the parties could not oust the overarching jurisdiction of the court by means of such an agreement. In this case reliance on the prenuptial agreement failed because the parties’ needs and circumstances dictated a different outcome. The most that can be said is that the Royal Court may hold that a nuptial agreement should be given decisive weight. However, this will depend on the circumstances of the case and the terms of the agreement. In G v. H [2018] JRC111 the Royal Court again rehearsed the legal principles set out in Radmacher and other leading English cases. While it is likely that these factors would be considered by the Royal Court were the matter ever to come up, a detailed analysis of the circumstances in which the Jersey court would be prepared (or not) to uphold a pre- or postnuptial agreement has not yet reached the court and the law in Jersey waits to be clarified. Those factors are:

- Whether the parties have freely entered into it, with competent legal advice and with a full appreciation of its implications.

- Whether the agreement might be vitiated by duress or freely entered into.

- Whether there has been a material lack of information or disclosure before entering into the agreement.

- Whether and to what extent the agreement provides the needs of the parties.

- Whether and to what extent the agreement provides for the needs of any children of the family.

- Whether the agreement and its terms are fair in all the circumstances.

International issues often arise in cases involving nuptial agreements. That is especially so in Jersey, which, as an international finance centre, is familiar with divorces where one or both parties have an ‘international lifestyle’ where assets are spread across the world in all manner of trust and corporate structures.

There is no Jersey authority on the question of whether it makes a difference if a pre- or postnuptial agreement must be governed by Jersey law to be given effect in Jersey matrimonial proceedings. The answer is likely to be that it makes no difference. The determinative factors that are likely to impact whether the agreement is given effect to or not are those listed above.

In Radmacher, the Supreme Court said that an English court will normally apply English law when exercising its jurisdiction to make an order for financial remedy under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, irrespective of the domicile of the parties or any foreign connection. The position in Jersey is likely to be the same.

2.1. Procedural requirements

The existence of a pre- or postnuptial agreement, its terms and the basis upon which it was entered into, are factors to which the court is bound to have regard under Article 29 Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949, as part of ‘the conduct of the parties to the marriage insofar as it may be inequitable to disregard it and to their actual and potential financial circumstances.’

2.2. Spouse’s financial claims

A pre- or postnuptial agreement can be entered into by spouses in respect of any part of the matrimonial ‘pot’ of assets, including assets not forming part of either spouses personal or joint estate (which would include assets held subject to a discretionary trust). It is not uncommon to see nuptial agreements that attempt to ring-fence trusts from the scope of matrimonial claims.

2.3. Children’s financial claims

A pre- or postnuptial agreement can make provision for financial claims regarding a child of the family (whether living at the time of the agreement or who are planned). If a nuptial agreement fails to do so, or fails to do so adequately that is a factor that will weigh heavily with the court in deciding whether or not to give effect to the agreement.

3 . The media and divorce/family law proceedings

The general practice in Jersey is that matrimonial and children proceedings are held in private (Royal Court practice direction RC 20/11). The information that can be published in respect of divorce cases is limited to the names, addresses and occupations of the divorcing parties and any witnesses, a concise statement of particulars, submissions and decisions on points of law and any judgment.

All children cases are held in private and nothing can be published which identifies or is likely to identify a child.

Members of the press do not have access to the Family division of the Royal Court. They do, however, have access to the published law reports, which are usually anonymised when they refer to children (and are increasingly subject to anonymity in any family matter).

It not usually the practice of the Royal Court to anonymise the names of professional trustees who may have become parties to divorce proceedings.

3.1. Reporting restrictions

Reporting restrictions will apply automatically to all matrimonial and children proceedings commenced in the Royal Court, which are, by default, held in private.

The mechanism by which the media may make applications to report on proceedings and having access to documents used in the proceedings is by way of an application to intervene and for access to be given to the court file, the pleadings and the affidavit evidence. The court’s accession to such request is extremely rare and is likely to be hedged with a number of restrictions (e.g. the identity of a minor or facts that would enable the identification of that child will not be permitted).

3-6 PQE Corporate M&A Associate

Job location: London

Projects/Energy Associate

Job location: London

3 PQE Banking and Finance Associate, Jersey

Job location: Jersey

James Sheedy

James Sheedy Simon Thomas

Simon Thomas